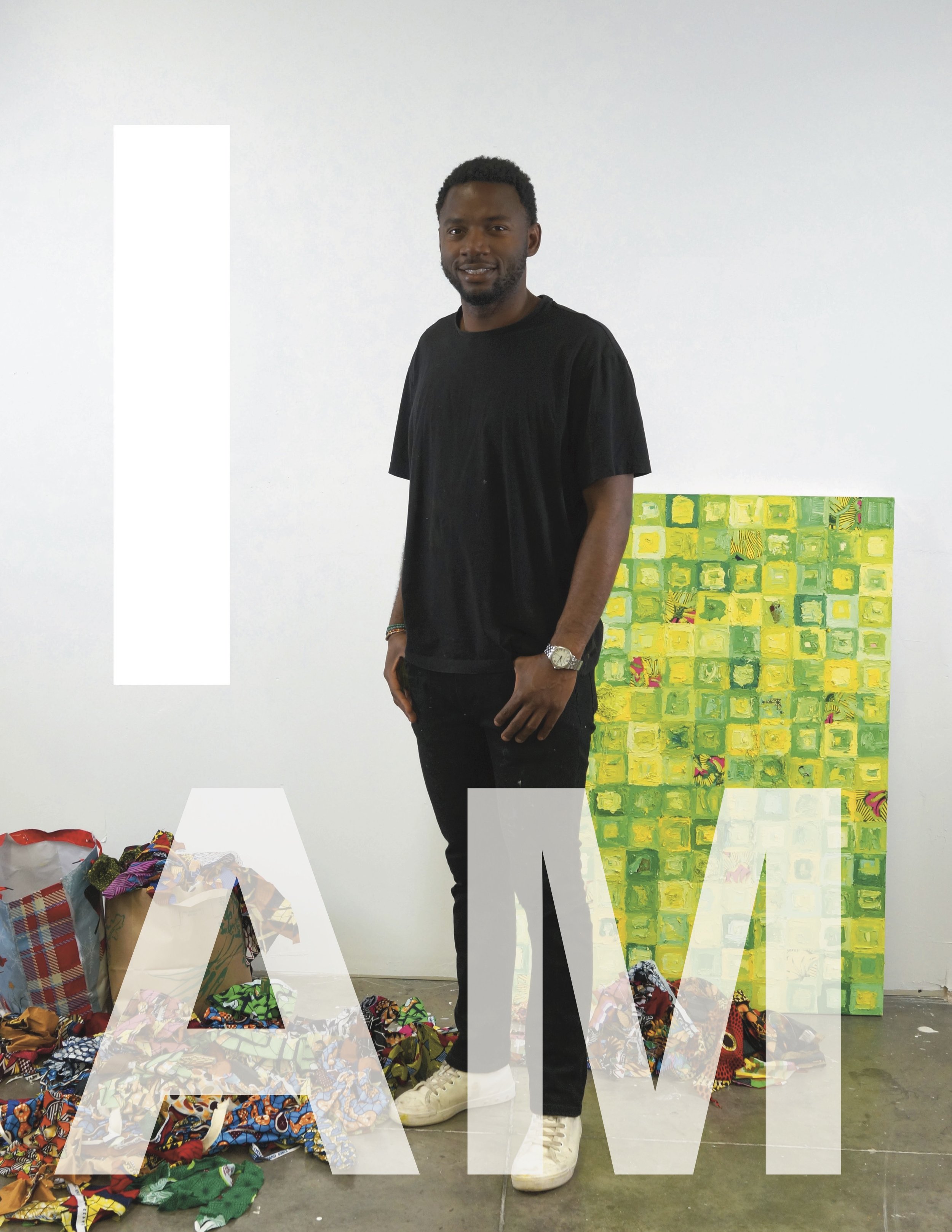

Jimi Kabela

Jimi Kabela Artist Statement

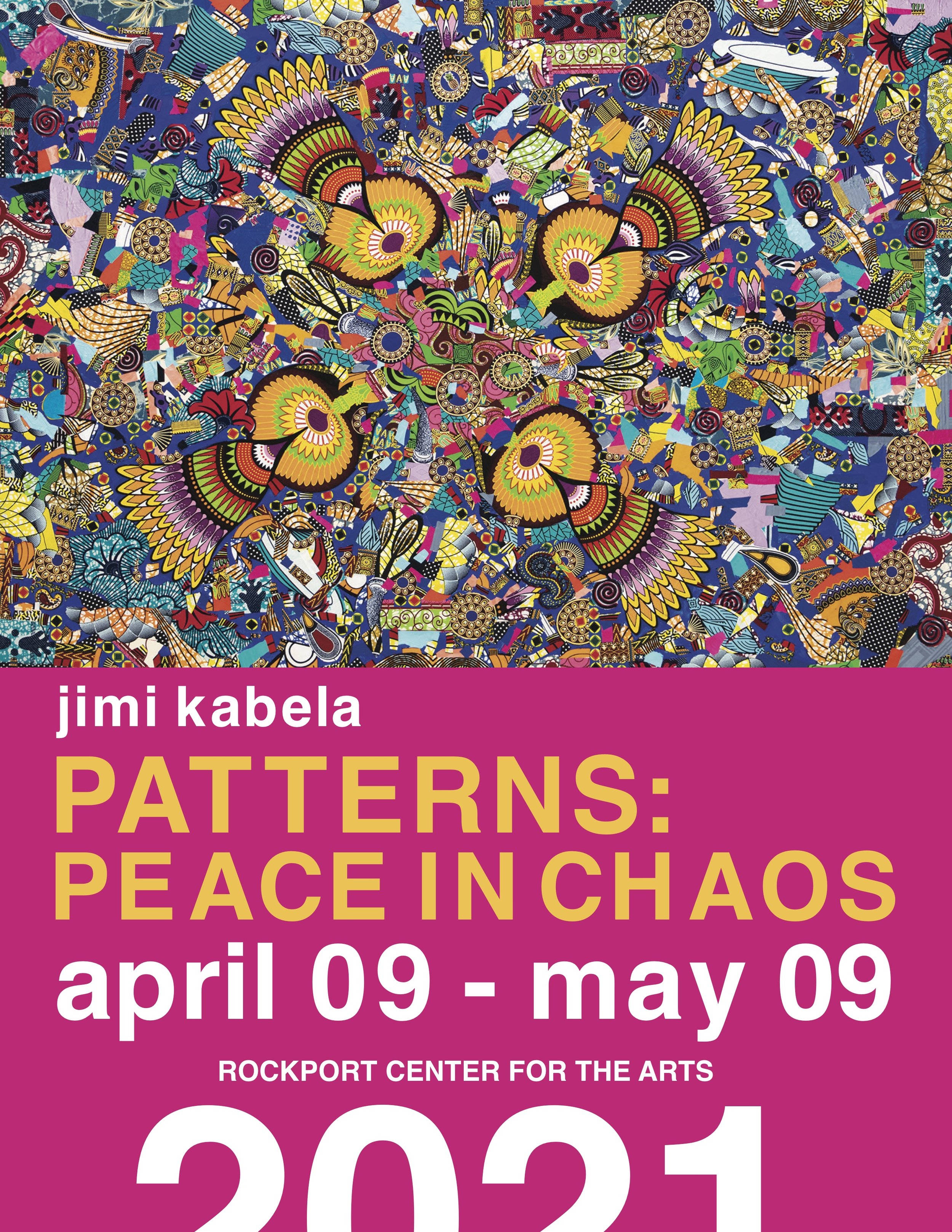

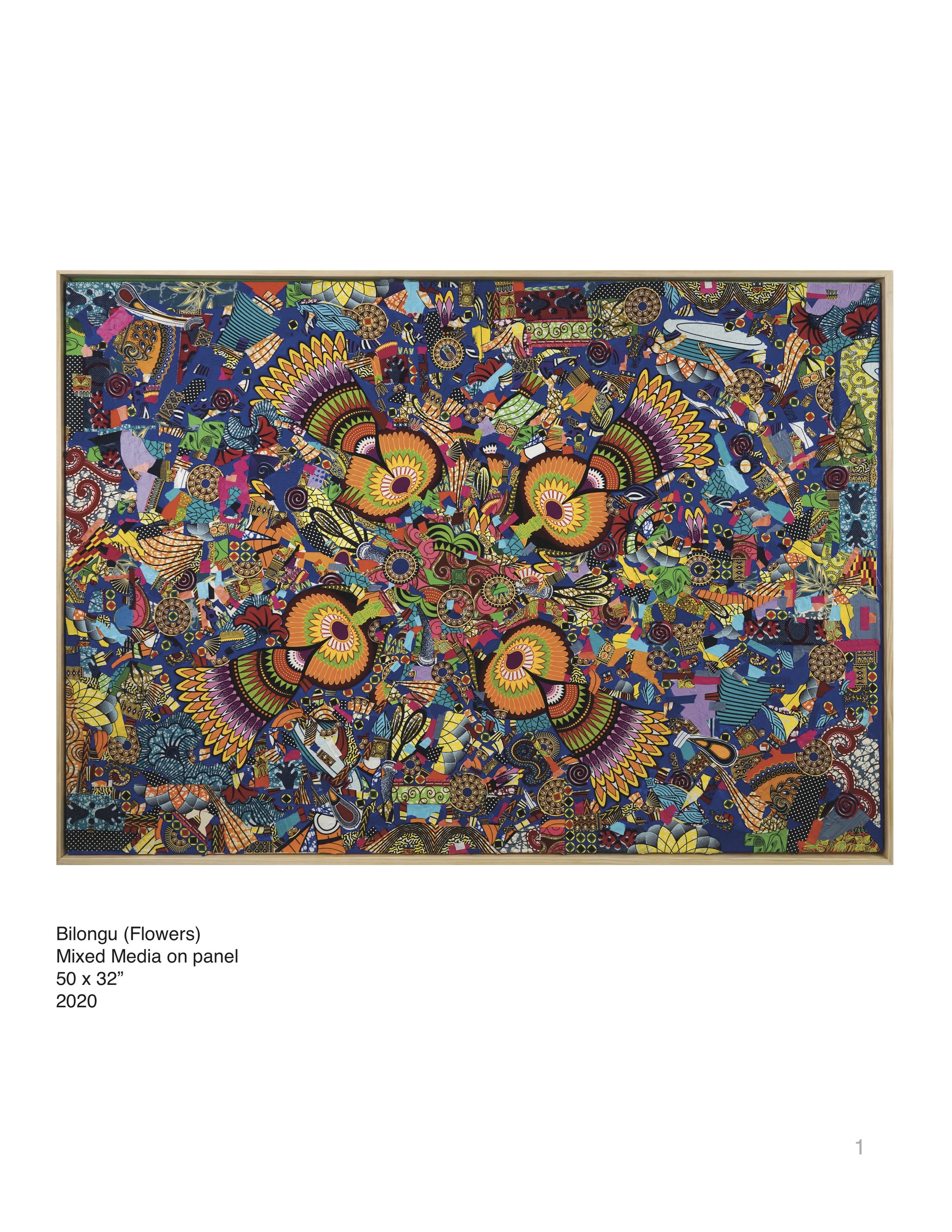

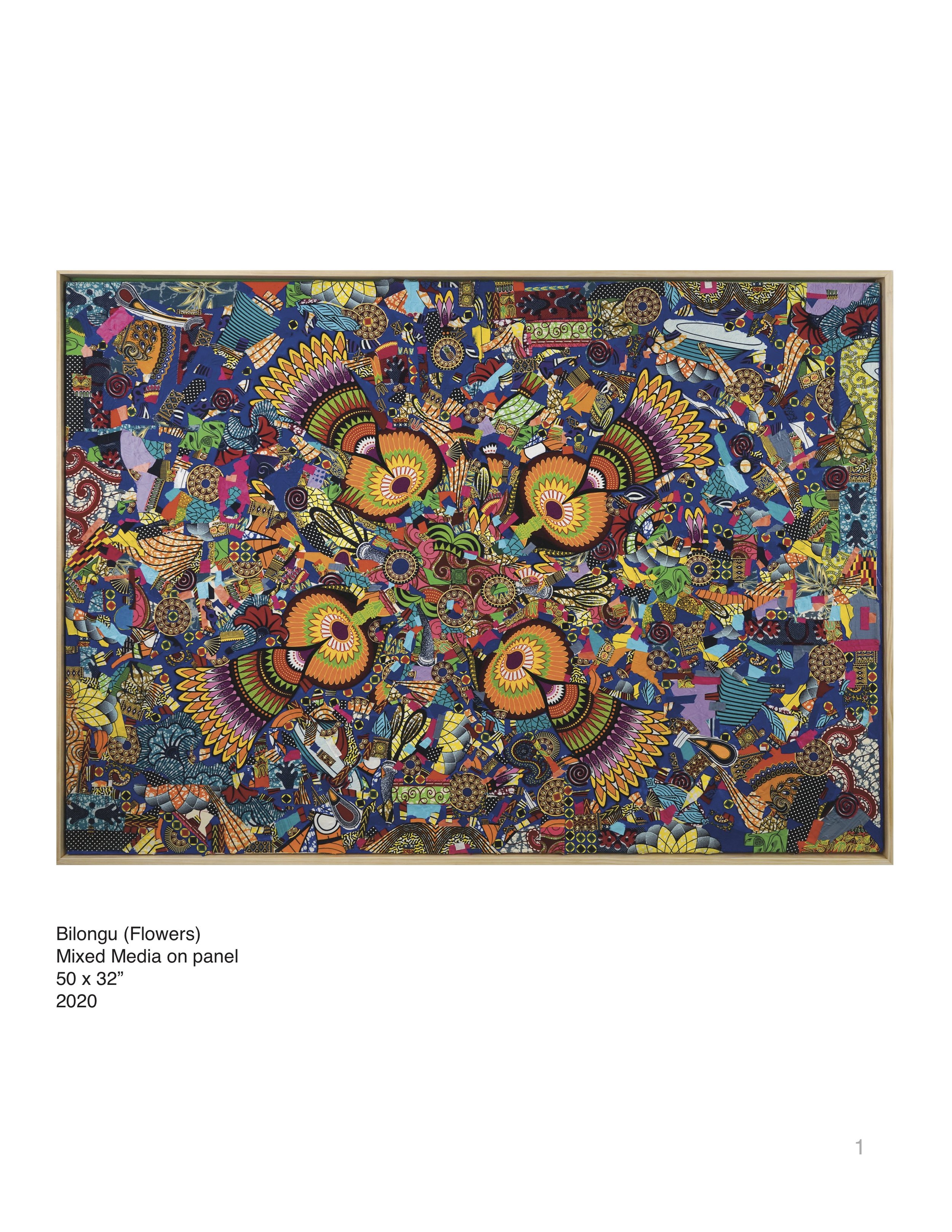

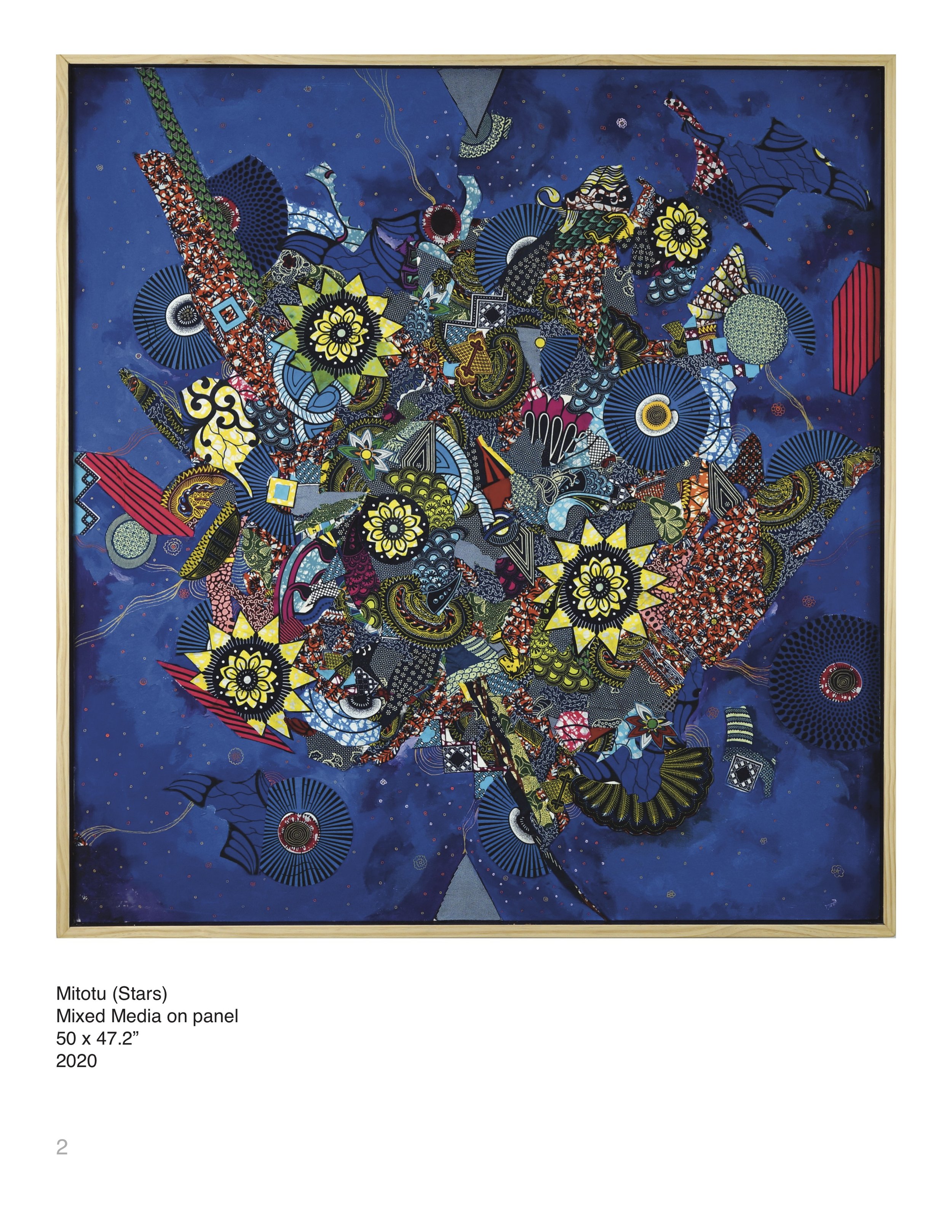

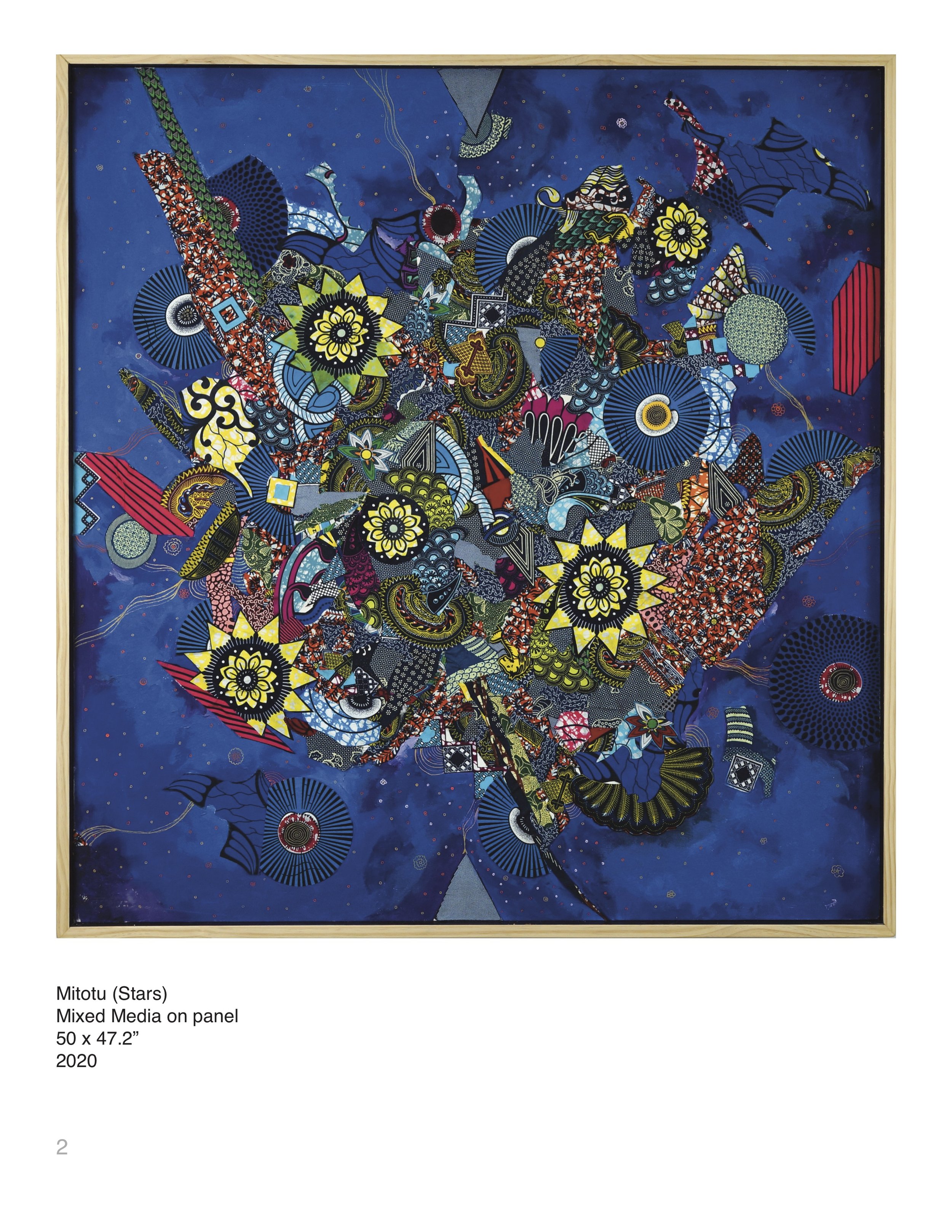

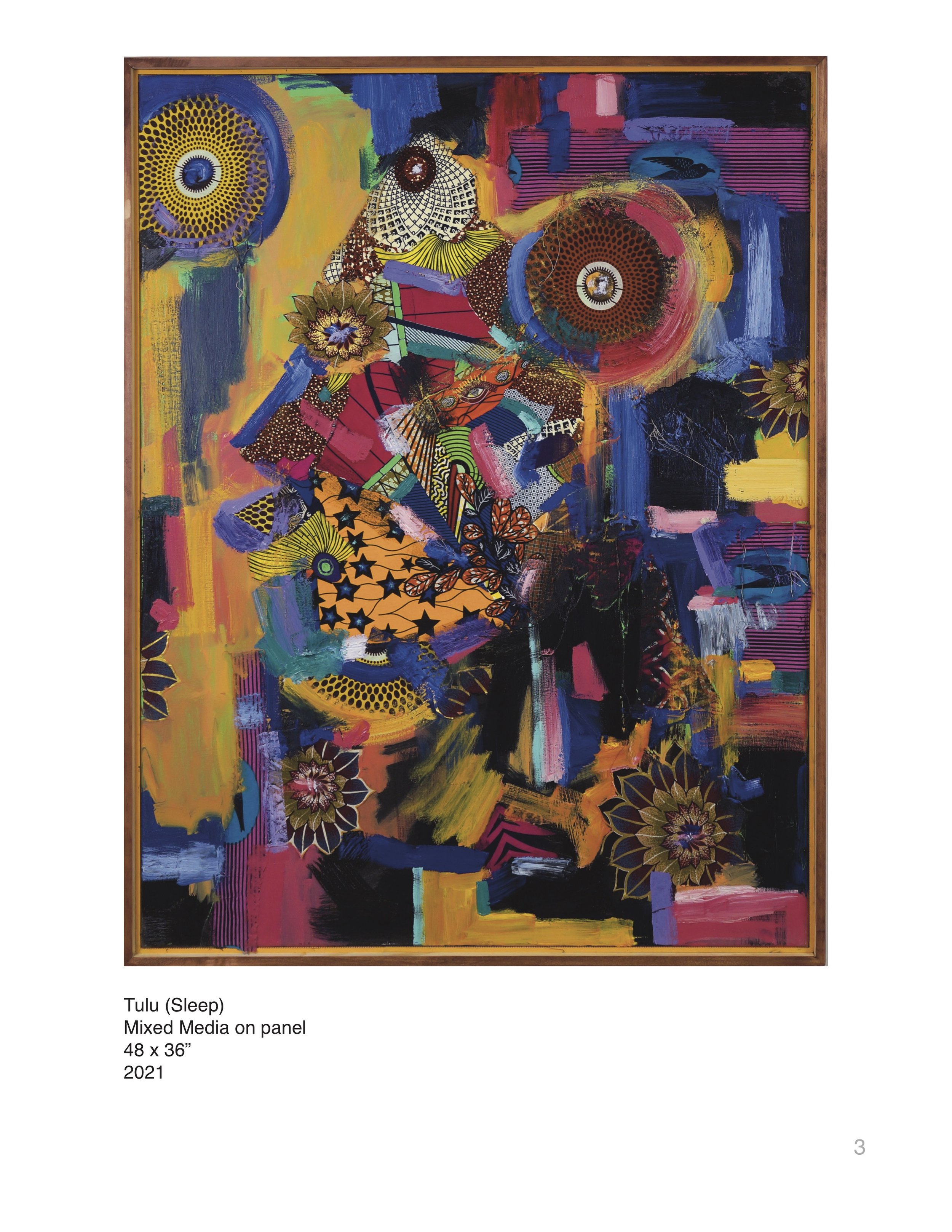

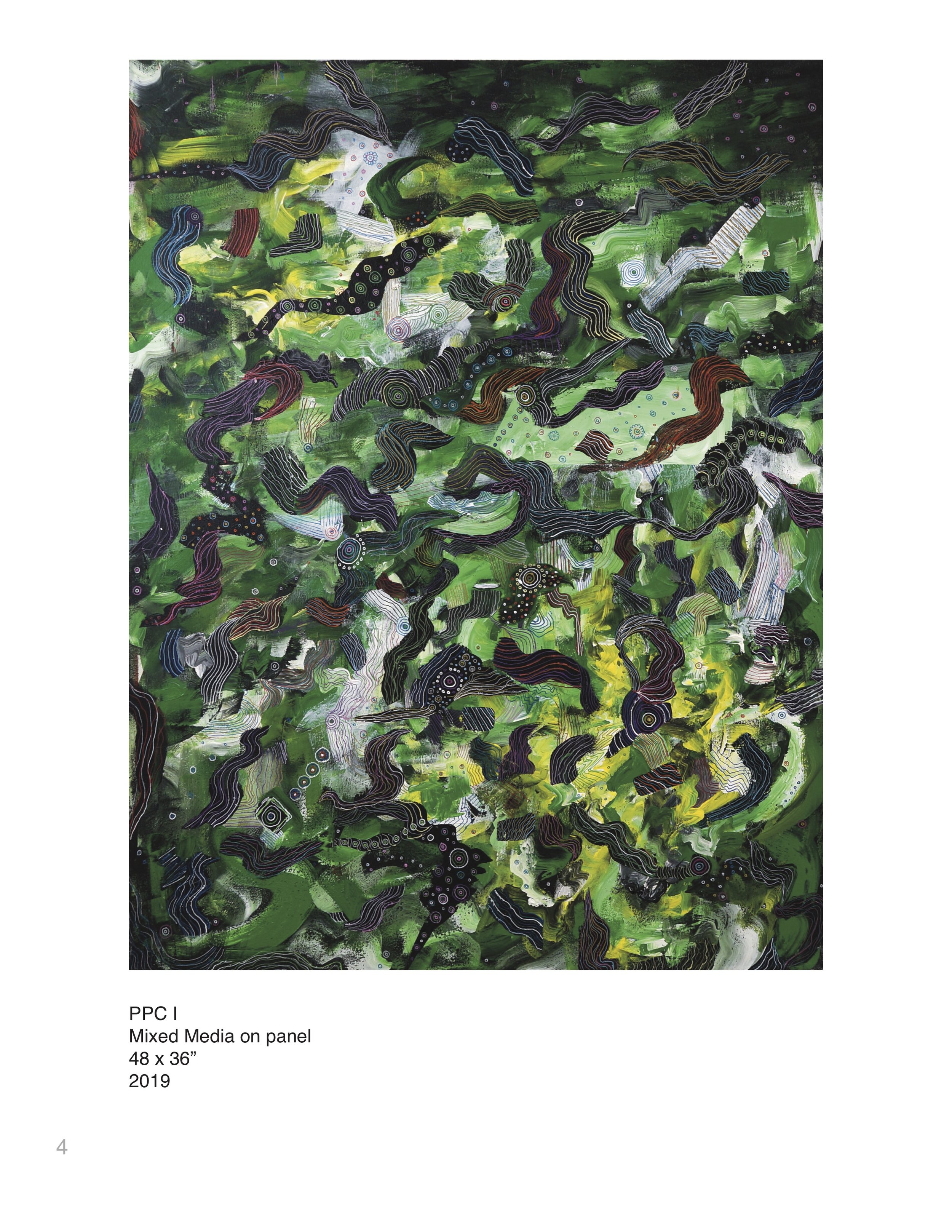

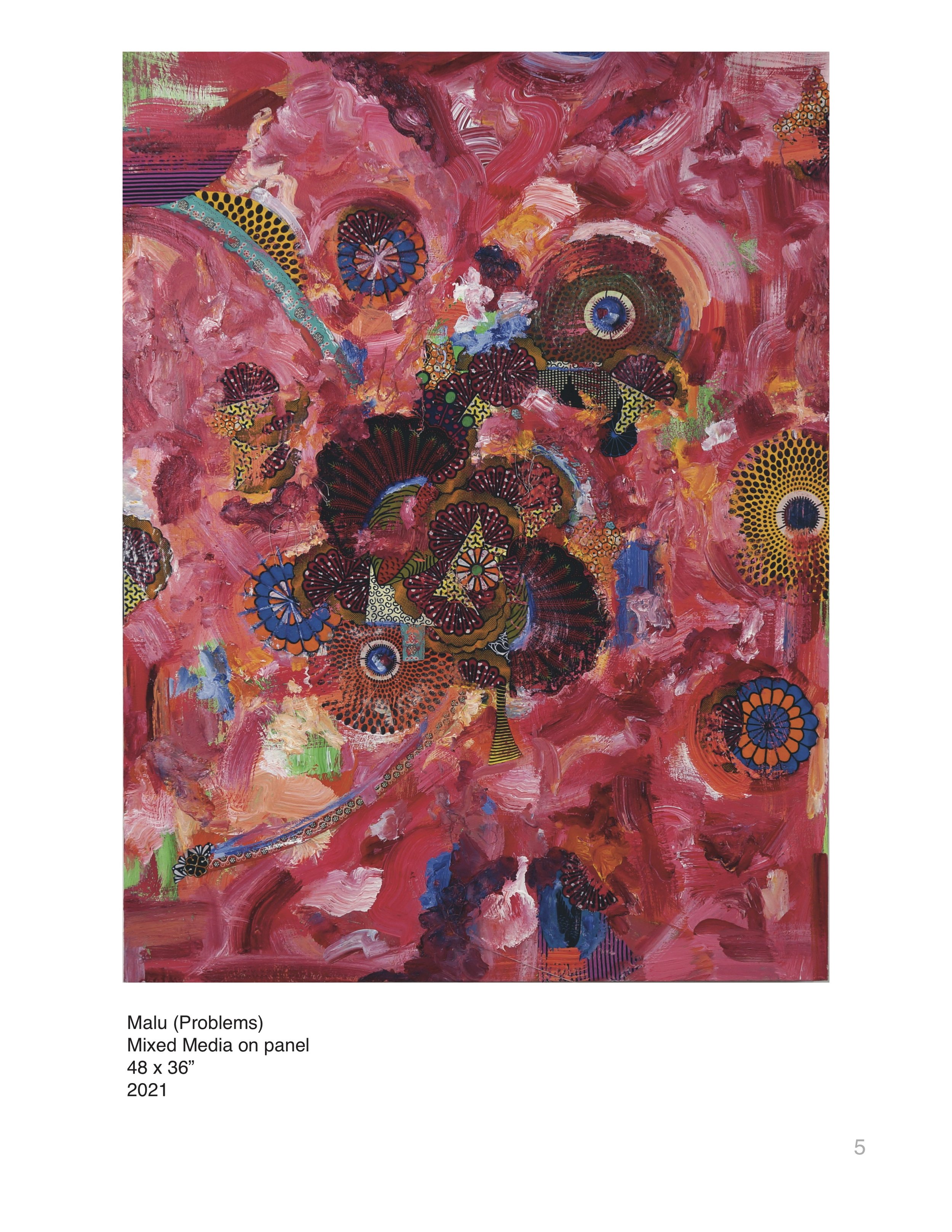

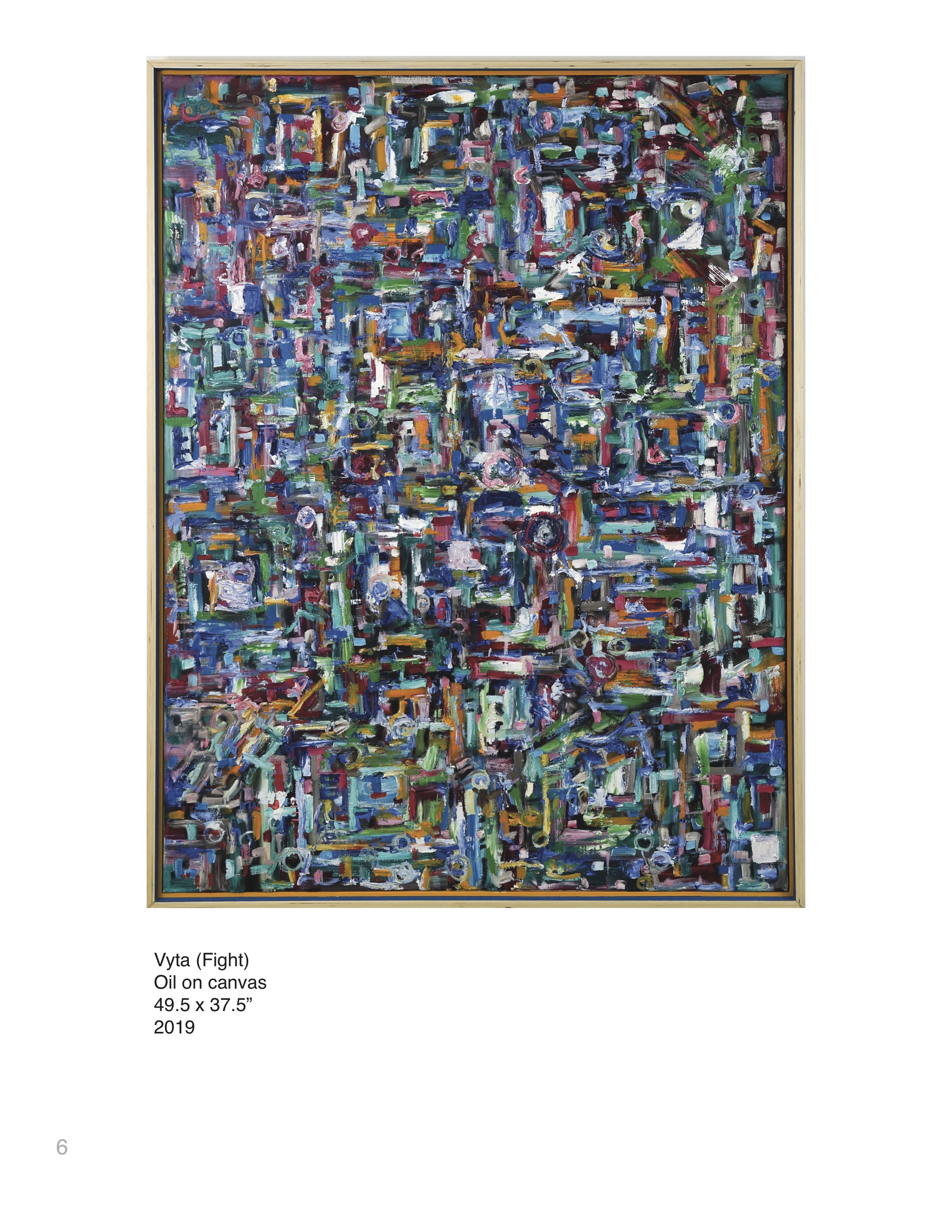

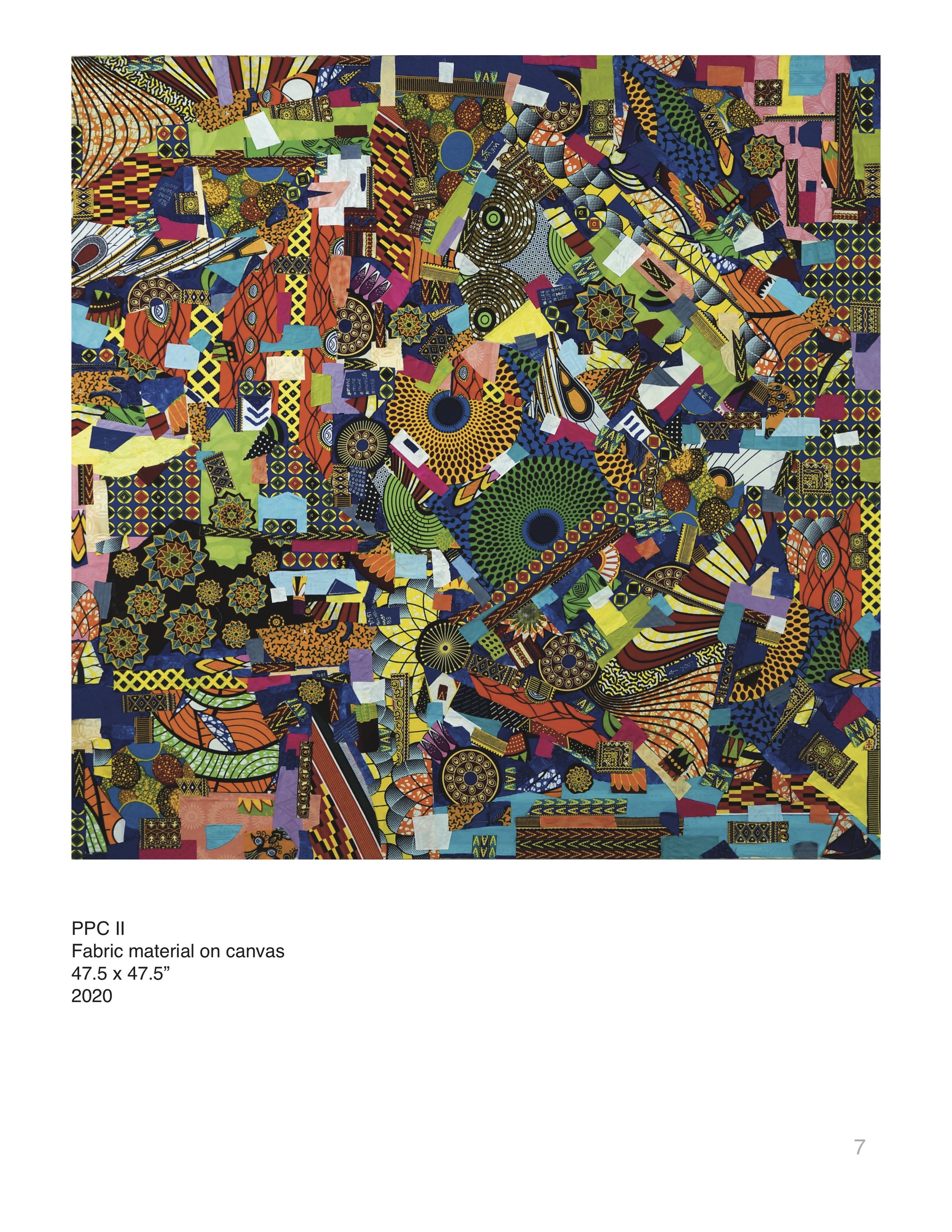

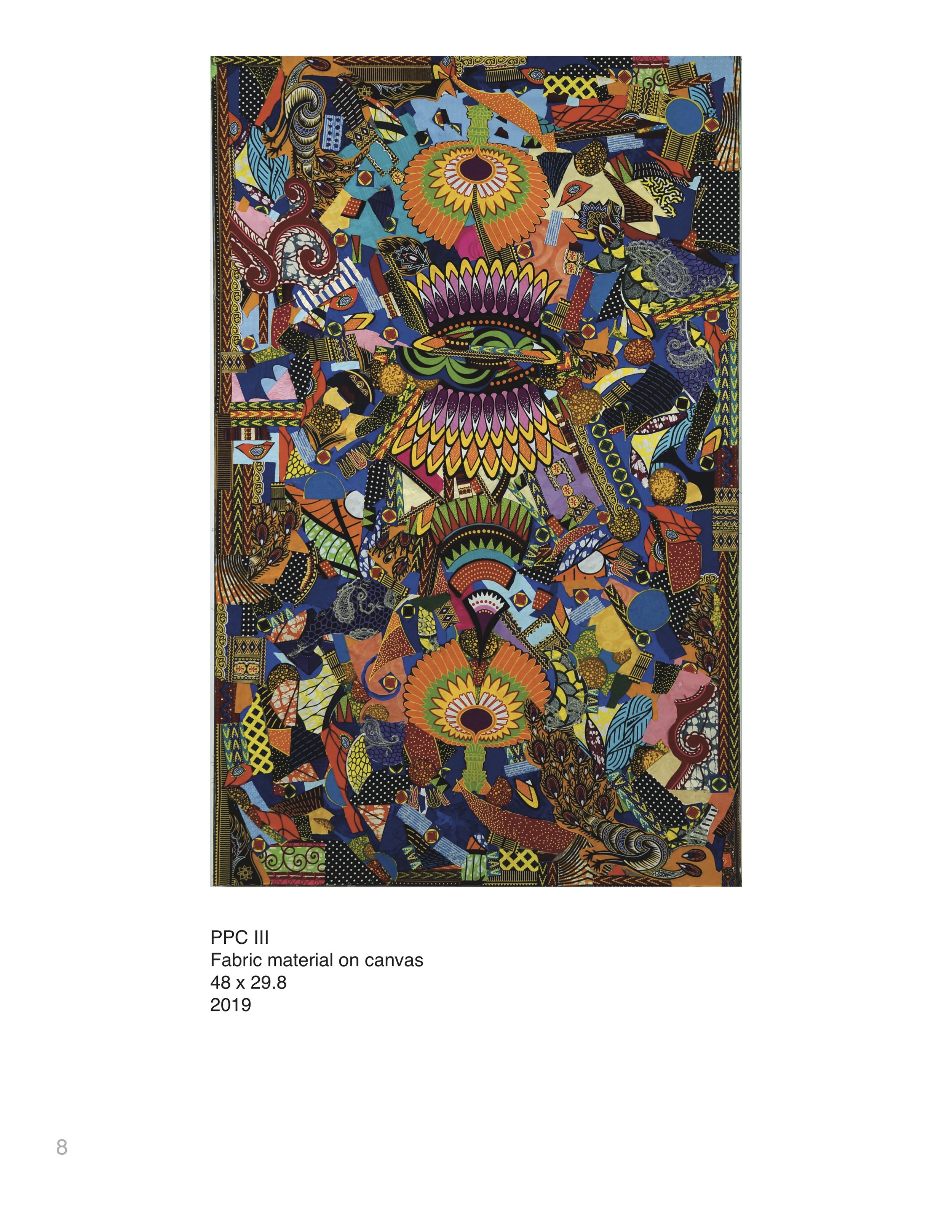

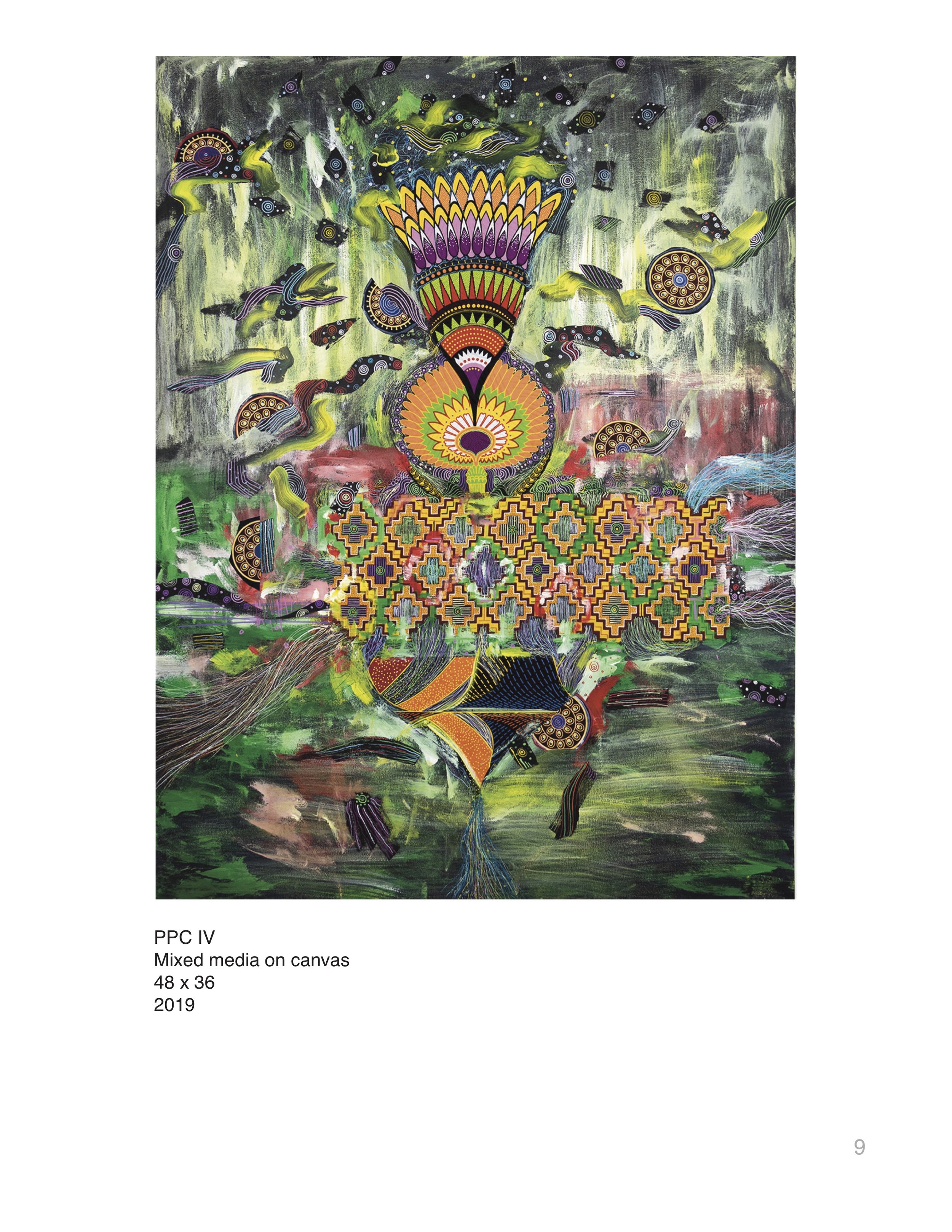

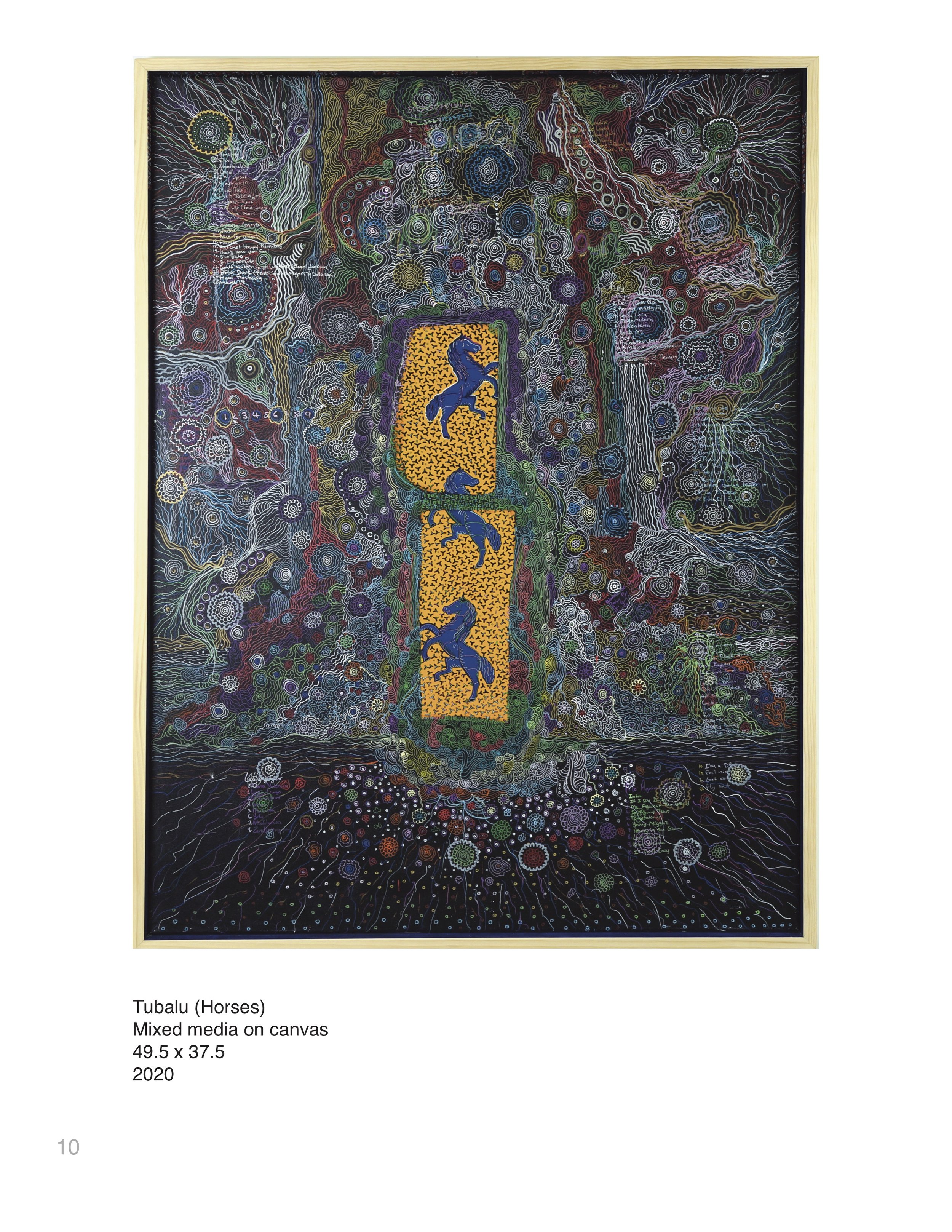

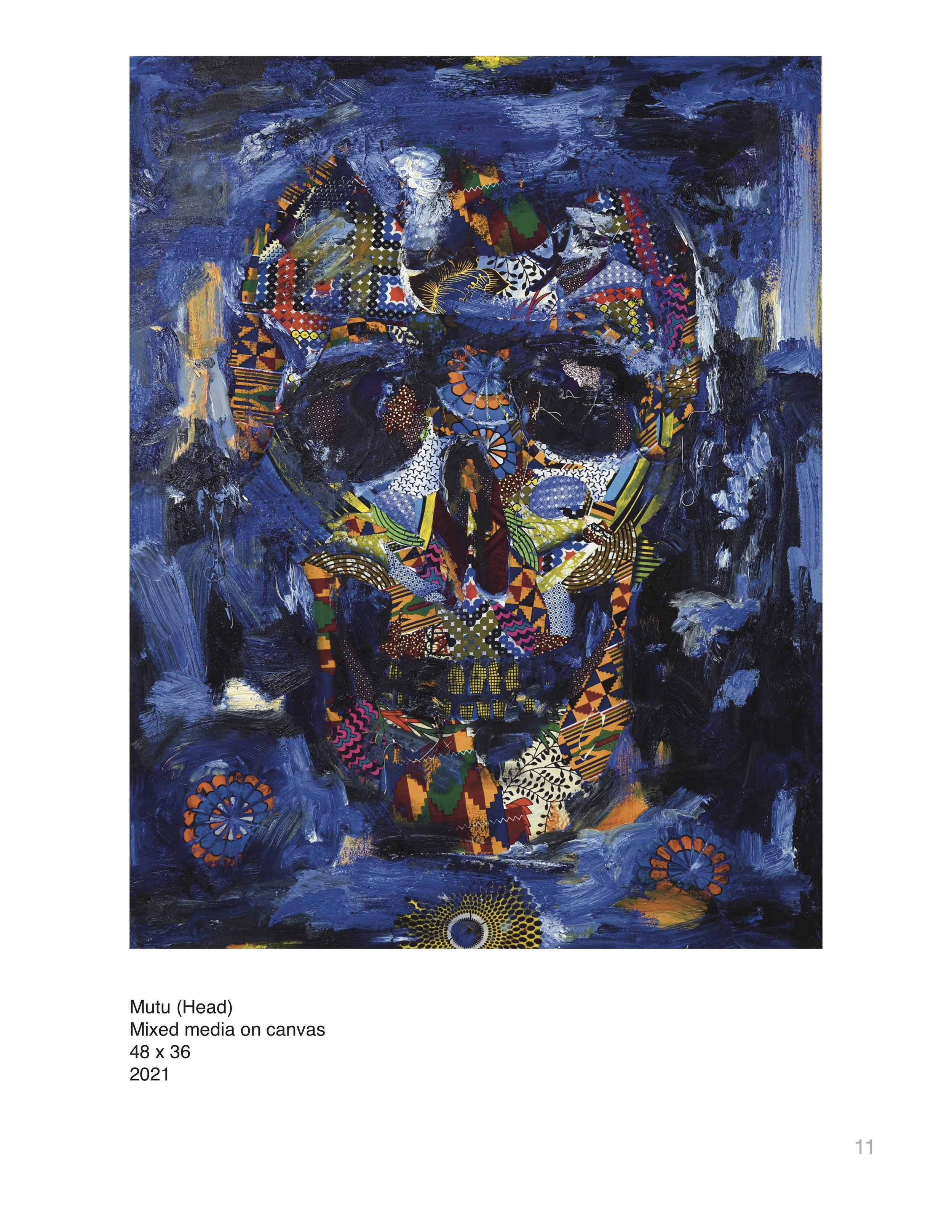

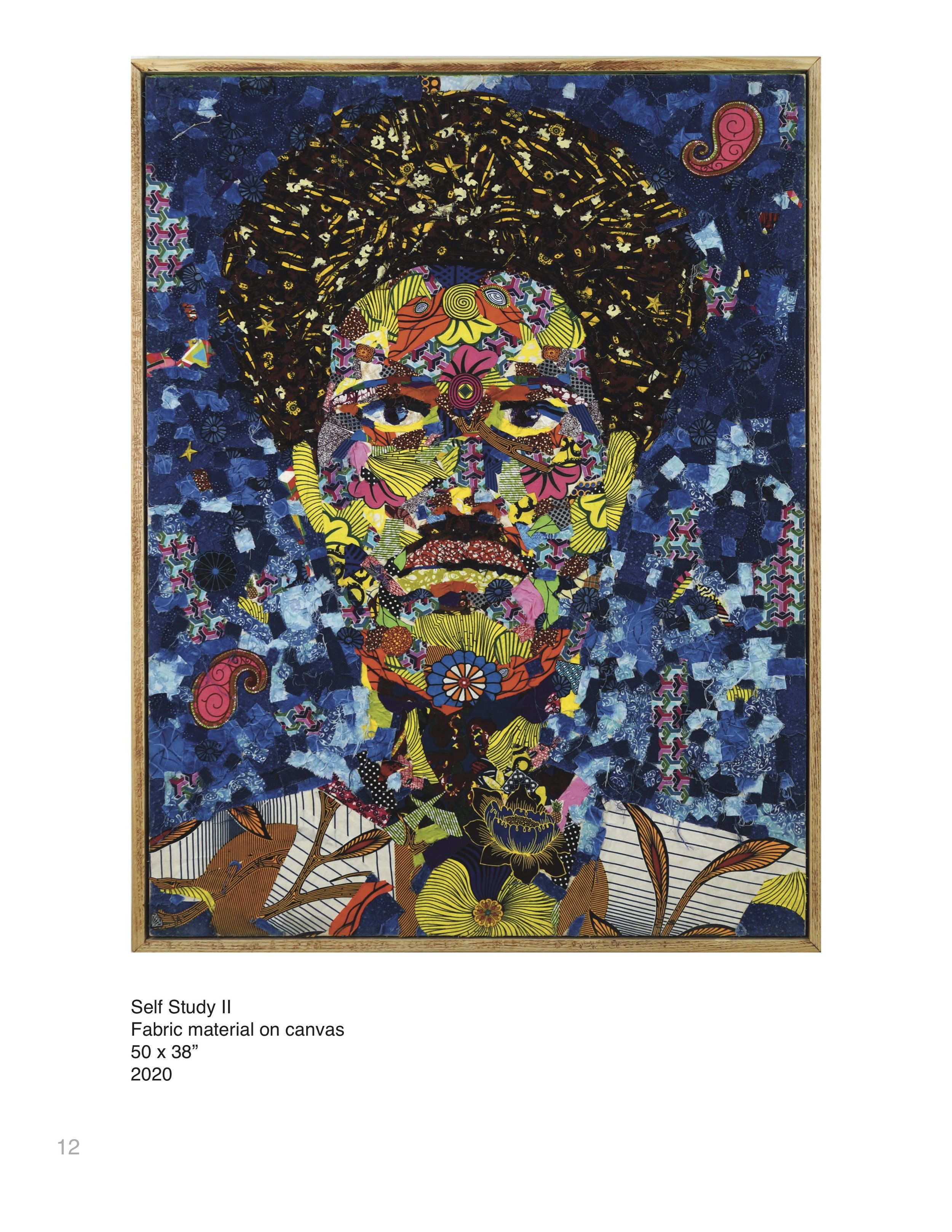

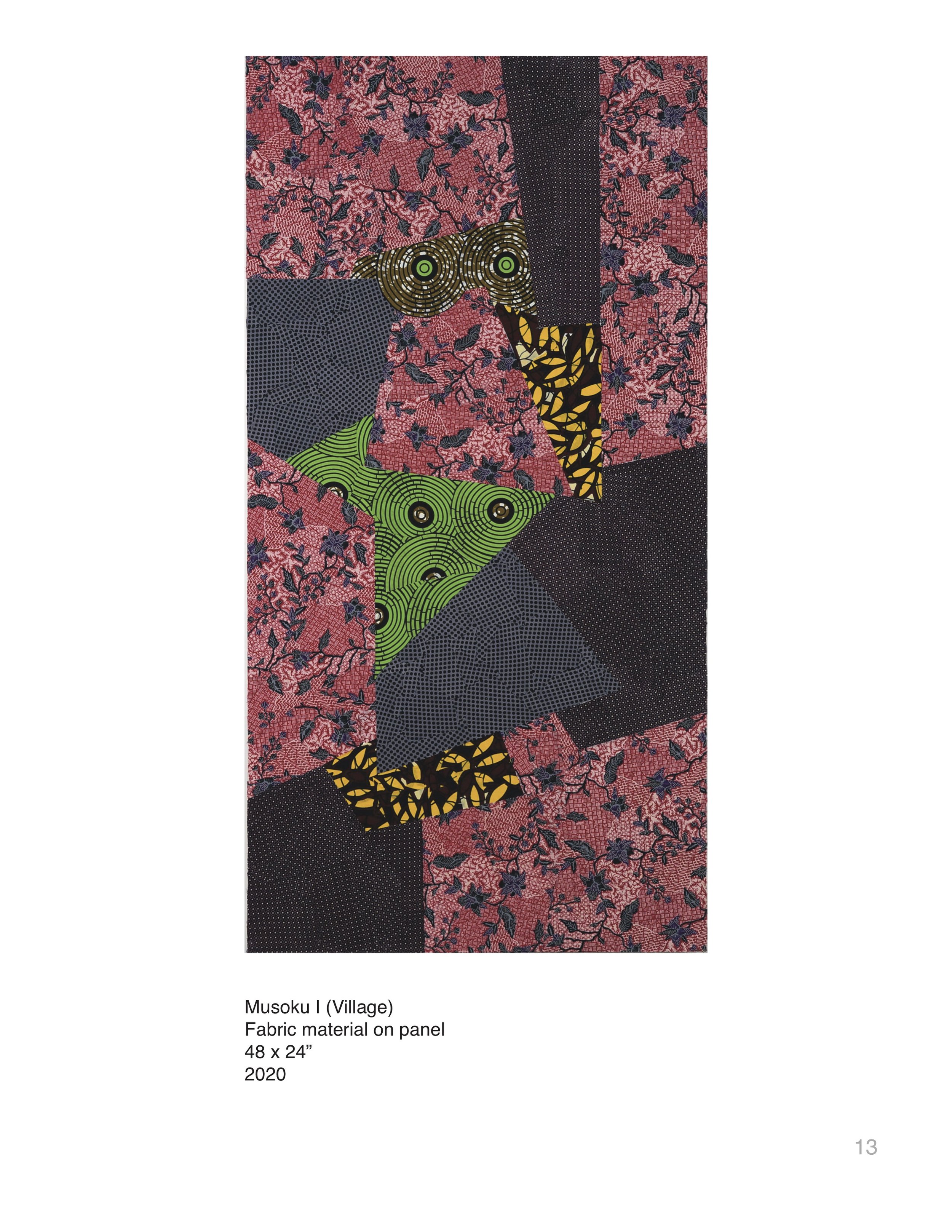

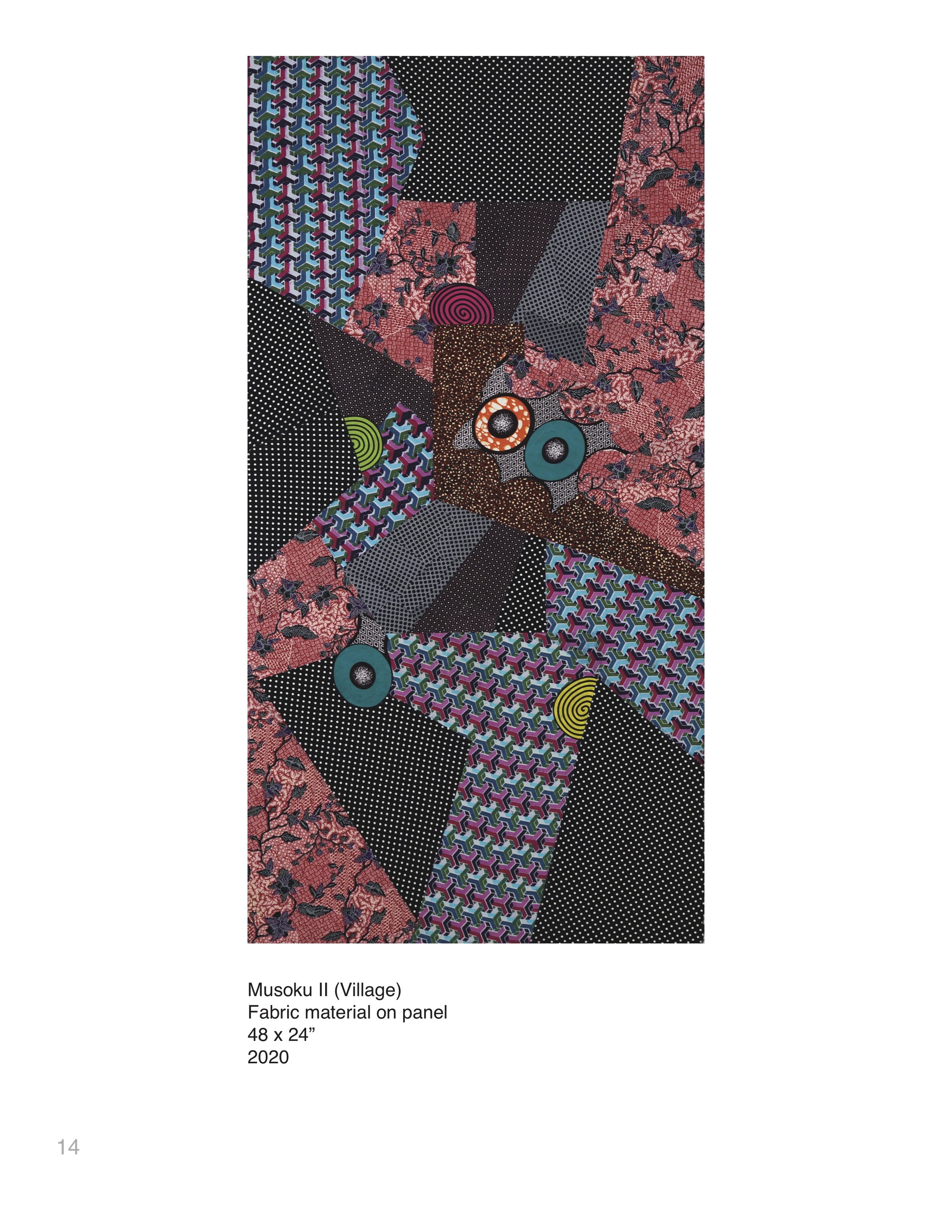

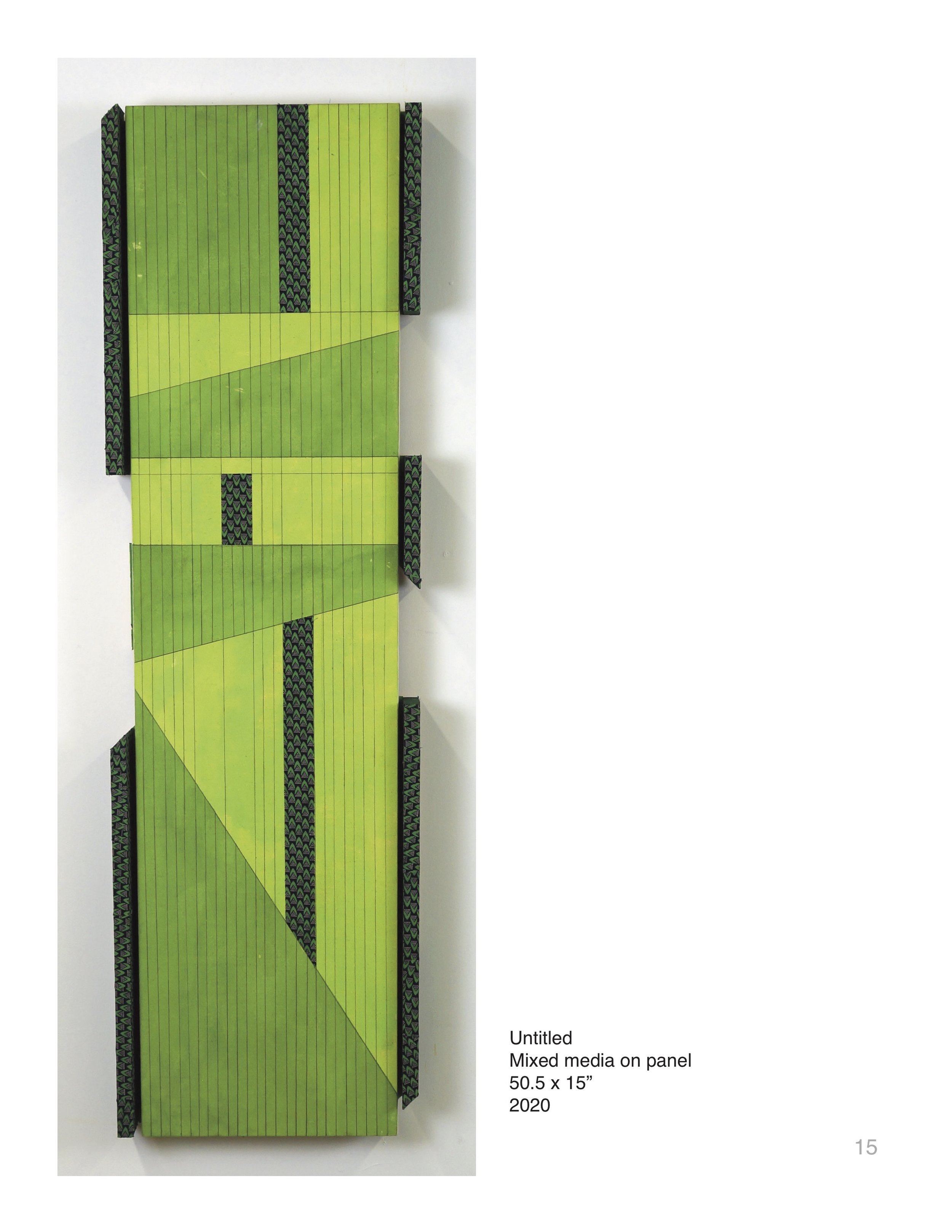

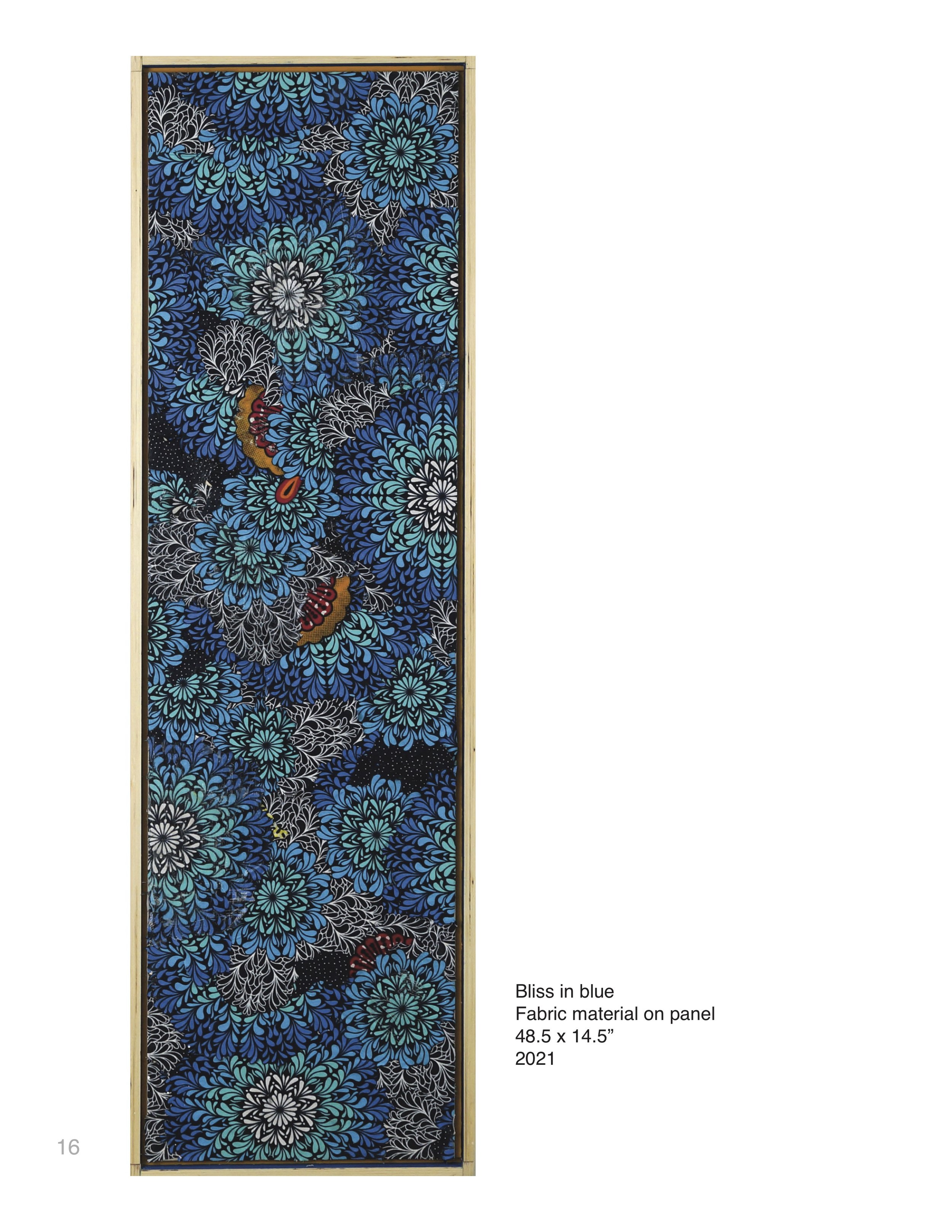

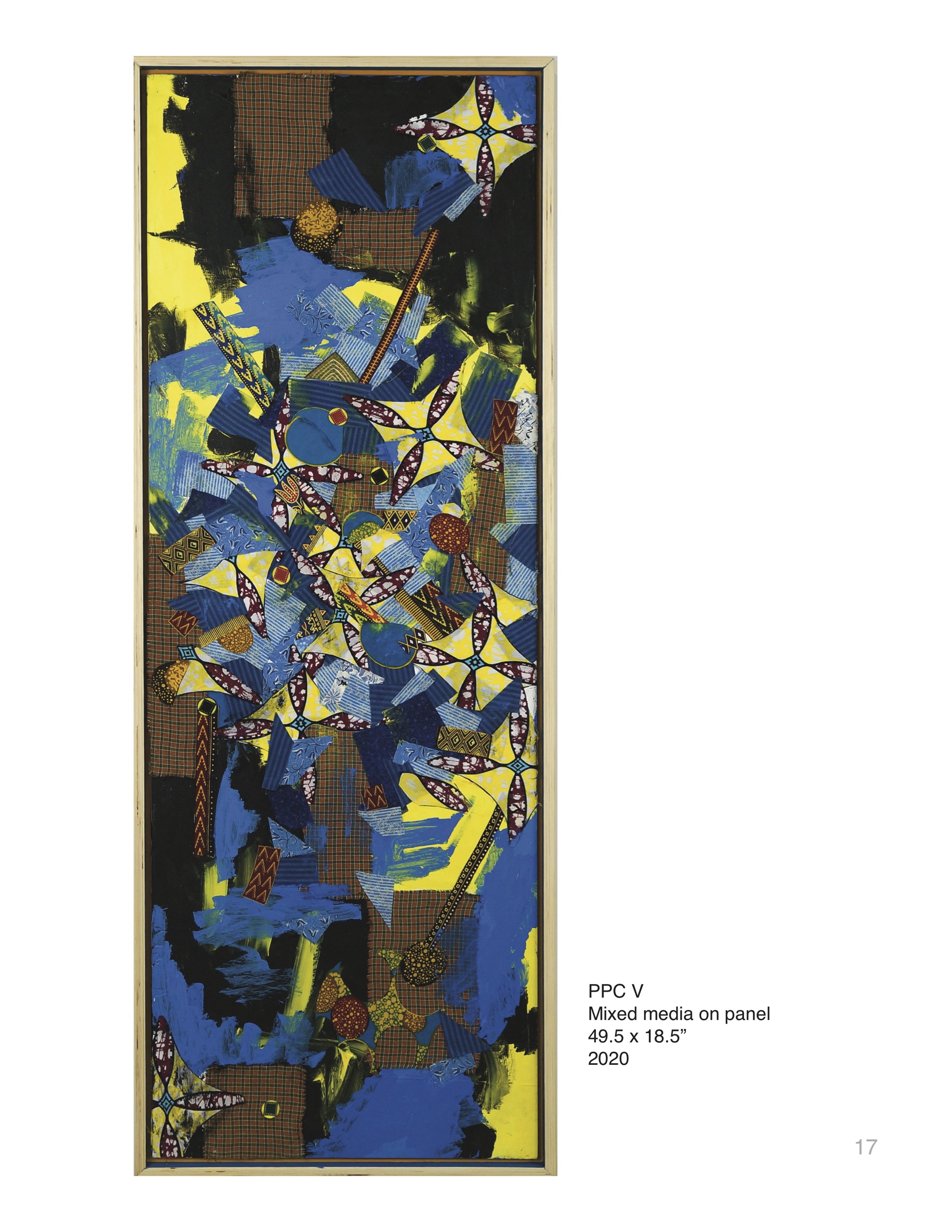

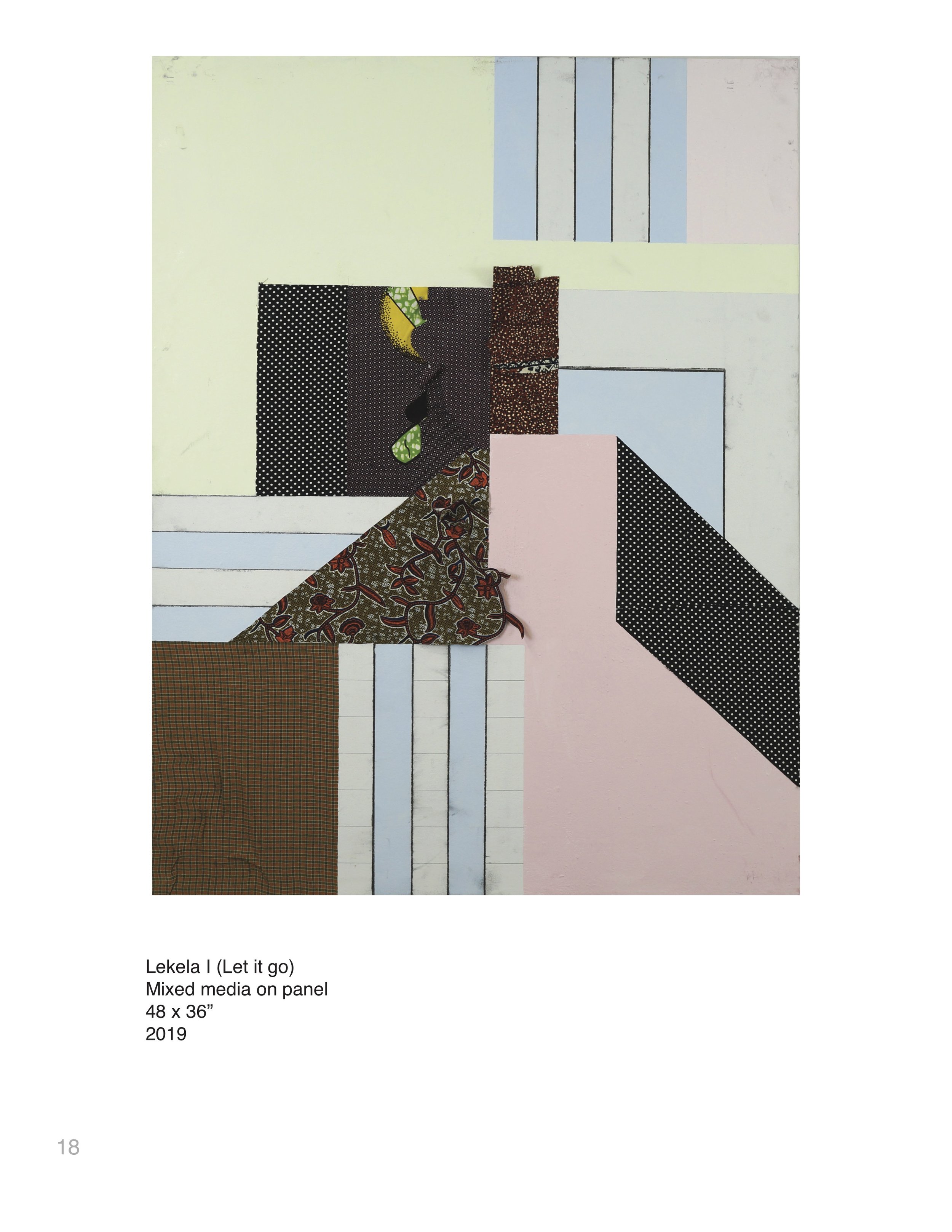

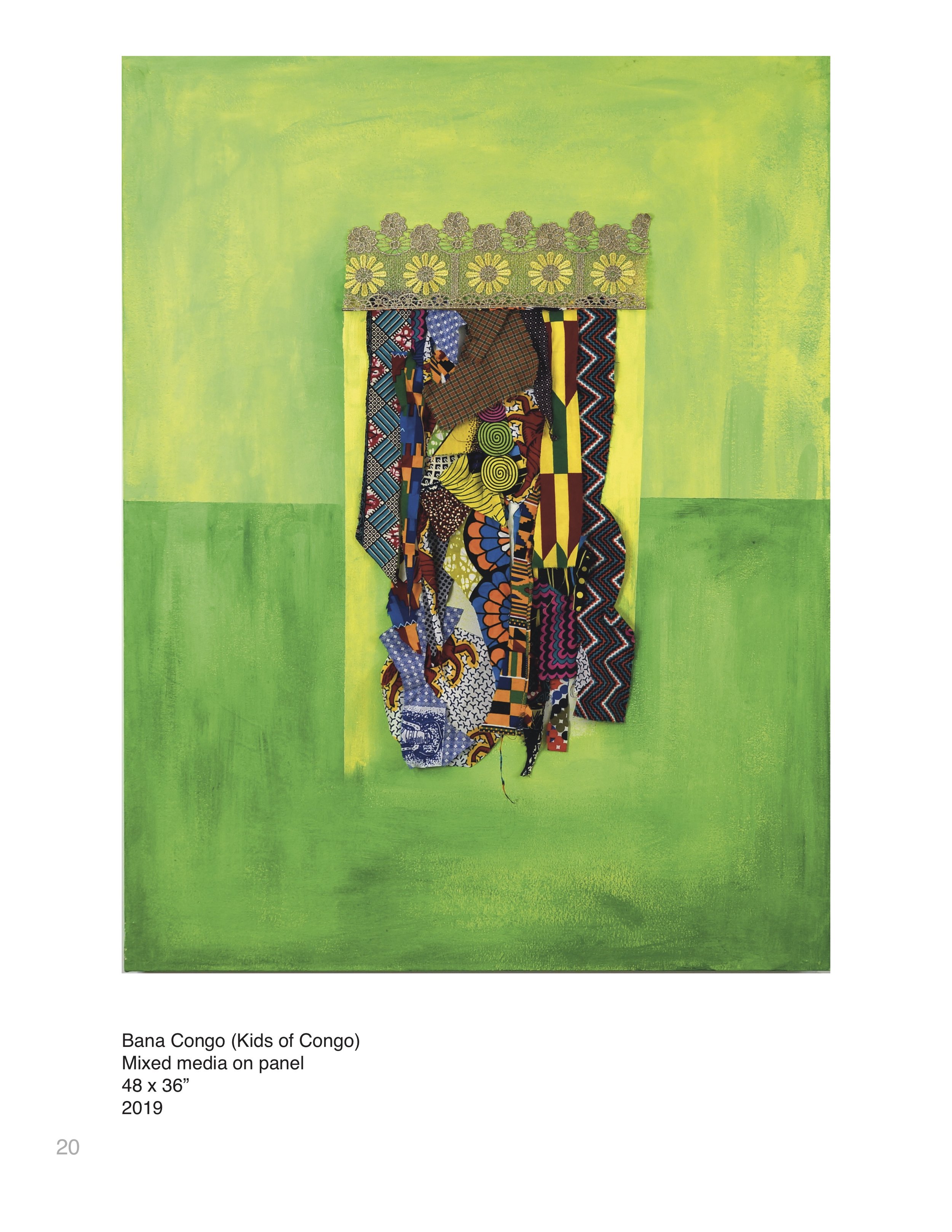

I use remnants of traditional African textiles and other items to express the Congolese and African roots of my birthplace. The bold, colorful patterns worn by the men and women of the Congo serve as a reminder of my ancestors, language, and origins. At the same time, my abstract paintings are influenced by my American experiences, specifically my upbringing in Dallas, Texas.

In my artwork, I seek to capture the complexity, positive rhythms, and energies of both African and American cultural influences. Through the process of collaging and abstraction, both with paint and African textiles, I am able to depict the duality of these cultures. My use of geometry and process in abstract painting serves to balance and harmonize these influences, creating a visual representation of my cultural identity.

Jimi Kabela – Q&A

Q: Can you tell us about your process in making your work?

A: I’d describe my approach more as a conversation—a kind of dialogue between myself, the canvas, and the textiles from the Congo that carry so much history within them. I’m new to this practice, so there’s a constant learning curve, where I’m questioning and experimenting, drawing on influences from my childhood in Mbuji Mayi, my experiences coming to America, and the various places I’ve traveled. Robert Motherwell once said that the function of an artist is to deepen the mystery, not solve it, and I relate deeply to that. Each painting emerges as its own exploration, not an answer.

Q: How do you source the fabrics you use?

A: The textiles I use are remnants from clothes that tailors would typically discard by burning. Three years ago, when I was accepted into the graduate program at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, I decided to make a trip to Kinshasa, the capital city of Congo, specifically to gather more textiles. After coordinating with family to set aside materials for me, I flew in for two weeks—everyone thought I was a bit crazy. Thankfully, I was able to collect enough fabric to last me through my time at Pratt, and I’m already making plans for another trip soon.

Q: Can you talk about the use of circles in your paintings?

A: For me, the circle carries a kind of symbolic weight; it’s a universal form found across nature and cultures. In creating this body of work for this exhibition, Amalgamation, I felt a need to introduce an amalgamate element to unify the textiles, paint, and typography. Circles began appearing intuitively—whether inspired by a recurring dream, a meditative moment, or even something as ordinary as the motion of slicing an onion; I don’t truly know how they came about. The circles have became an amalgamation of holding everything together, like a quiet language woven through each piece.

The circular form is open to interpretation; it gives viewers a pathway to explore, almost as if each circle serves as an invitation to travel within the work. One friend even suggested they evoke a sense of spiritual movement, as though the circles serve as "angels" or points of guidance, which feels beautifully fitting.

Q: How about the numbers (typography) in the paintings?

A: The typography in my work stems from a love of typeface that I developed during my undergraduate studies at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA). In that typography class, I was introduced to the nuances of type as both art and design, which was a revelation. I became particularly captivated by Max Miedinger’s Helvetica and the way its clean, modern lines transformed the New York subway’s visual language. Helvetica’s simplicity and structure have a timeless, universal quality that resonated with me, and numbers became a personal language as well—a way to reflect aspects of identity that are often invisible yet essential, like phone numbers, social security, driver’s license numbers, and so on. In a sense, numbers hold a constant presence in our lives, and incorporating them into my work has allowed me to explore how these symbols of order and structure intersect with our everyday life.

Q: What music do you listen to when you work?

A: Growing up, music was a constant in my life, though no one in my family played instruments. I discovered it through my father, a businessman who traveled the world. Wherever he went, he’d bring back vinyl, cassettes, or CDs—sounds from the places he’d visited. As a child, I’d get lost in the rhythms, often not understanding the language but feeling the energy of distant cultures.

One vivid memory I have is from when he returned from New York in the 90s. He brought back music by Michael Jackson and Marvin Gaye, along with photos of skyscrapers, the Statue of Liberty, and city scenes. These songs and images became windows to other worlds, helping me appreciate the beauty of diverse places and perspectives. Even now, my taste in music remains eclectic, with tracks that transport me to different times and cultures, grounding me in my work and sparking inspiration.

Q: How did you first become interested in art, and becoming an artist?

A: My first experience in a museum was actually when I came to New York at 17. I was curious about the city, especially the Times Square New Year's Eve countdown, and wandered into the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) out of pure curiosity. That experience stirred something deep within me. Wandering through MoMA, I found myself standing in front of Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, The Sleeping Gypsy by Henri Rousseau, and a striking drawing of a woman by Charles White. I can’t recall every detail, but I remember how those pieces didn’t just captivate me visually; they connected to something more profound. They allowed me to step outside of my own reality and glimpse something beyond—something that made me question my own existence.

At the time, I didn’t imagine myself as an artist. That path began a few years later, while I was studying at Tarrant County College. One day, I found myself in a hallway, watching professor Christopher Blay installing work for a student exhibition. I remember critiquing a painting that didn’t look quite complete to me. The professor overheard and, intrigued by my thoughts, asked if I painted. I hadn’t touched a brush at that point, but he suggested I try a painting class. Fortunately, I was able to enroll in Professor James Goebel’s introductory painting course, and it was in his classroom that I started to learn the fundamentals: mixing colors, shading, capturing still life, and all the basics. But more than that, I found a sense of freedom. In Professor Goebel’s class, I wasn’t restricted to assignments; I could explore any subject that spoke to me. I experimented with landscapes, animals, objects, and people. My paintings weren’t masterpieces—most of them were far from it—but I was discovering something transformative about the act of painting itself.

At that time, I was pursuing a business degree, balancing a job, and running a small computer store. Art was just an elective, something I enjoyed, and I enrolled in Professor Goebel’s classes as often as I could because they filled me with a sense of joy I couldn’t find elsewhere. After Tarrant County College, I went on to study business at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA), convinced that this practical route would offer security and a stable career. Yet, even with that logical decision, I felt hollow.

Then, as an elective, I signed up for a figurative painting class with Professor Sedrick Huckaby. His work in portraiture—a style that, with its thick impasto layers and tangible texture, gave skin an almost touchable quality—profoundly impacted me. There was a depth to Sedrick’s work that was more than just an image; it felt alive. Watching him paint, I began to understand that a career as a painter was possible and that I could create something meaningful. I was a semester away from finishing my business degree when I took the leap of faith to switch into the bachelor of fine arts program with a minor in painting. I wasn’t entirely sure what painting held for me, but I knew I had to try.

Sedrick became both a mentor and a guiding influence, but as much as I admired his mastery in figurative painting, I didn’t feel ready to achieve that depth in my own work. So I began to explore abstraction. In my attempts to express myself freely, I embraced colors, shapes, and forms that felt like they belonged to me. Abstraction gave me the space to experiment, to break away from what I felt I couldn’t yet achieve in portraiture. I see my journey as a continuous path. I may have started in abstraction, but I feel I’m simply making my way forward, layer by layer, as I work toward bringing that same depth to my own work in the future.

Jimi Kabela UTA interview