Museums Correspondent

Two years ago, the works of artist Hung Liu were readied for a major exhibition in China, the country of her youth. Mere months from opening day, the show was censored by the government, import permits denied.

Liu’s adopted homeland is much more open-minded and forgiving.

A retrospective exhibition "Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands" at Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery features Liu’s autobiographical paintings and images of nameless outcasts—migrants, refugees, orphans and prostitutes—in which she seeks to give voice to her marginalized subjects. The first major show of Liu’s work on the east coast after years of acclaim closer to the Pacific, where for more than two decades she was a professor at Mills College in Oakland, California, is also the first retrospective for an Asian American woman artist at the museum.

In 1980, Liu was admitted to the University of California, San Diego, where she studied with Allan Kaprow, who had pioneered “Happenings,” spontaneous acts of performance art. She attributed her improvisational painting style to that early influence. Reproduction after the original 1980 photograph. Courtesy of Hung Liu and Jeff Kelley

Liu died just weeks before the show’s opening of pancreatic cancer, leaving us to remember how even as she chafed under the burden of history, her own and the disenfranchised, she emerged triumphant.

She painted resilience, and with resilience.

On view is a 1993 self-portrait that was one of the more than 30 paintings originally slated for the exhibition in China at Beijing’s UCCA Center for Contemporary Art; it was withdrawn in an effort to appease authorities. Based on a tiny photograph, the robust artist is dressed for mandatory military training during Mao’s Cultural Revolution with a rifle slung over her shoulder and a vest of tactical gear affixed to her chest. Titled Avant-Garde, the monumental shaped canvas alludes to Liu as a “guard” of a socialist reality she did not condone. The shimmering blade of her bayonet is a sly reference to Claude Monet’s 1872 Impression Sunrise; orange brushstrokes mirror the reflection of Monet’s brilliant titian sun hanging over the water. This was the painting that gave the avant-garde Impressionist movement its name.

The early self-portrait that so disturbed the Chinese government was prescient for Liu’s future artistic trajectory: an historical photograph as source material, a shaped canvas and a woman as warrior. “All the women she painted have a presence and agency about them. Liu’s work is groundbreaking in both subject and style. Her art is a collision of the ancient and contemporary, the east and the west,” says exhibition curator Dorothy Moss.

Strange Fruit: Comfort Women by Hung Liu, 2001 Karen and Robert Duncan Collection. © Hung Liu

“I paint from historical photographs of people; the majority of them had no name, no bio, no story left. Nothing. I feel they are kind of lost souls, spirit-ghosts. My painting is a memorial site for them.”

Anonymous women most frequently occupied Liu’s imagination as she strove to recover and recognize their stories of pathos, and just as much their strength. “I paint from historical photographs of people; the majority of them had no name, no bio, no story left. Nothing. I feel they are kind of lost souls, spirit-ghosts. My painting is a memorial site for them,” Liu said in a 2020 interview.

Born in 1948, Liu grew up in Changchun, China, primarily raised by her mother, grandmother and aunt; her father was imprisoned when she was an infant for serving in the Nationalist Army, and she did not see him again for almost 50 years. In her early 20s, forced to labor with peasants in the countryside as part of her proletariat reeducation, Liu found refuge by secretly sketching villagers in pencil. During her four-year exile, she began also experimenting with a camera, left with her for safekeeping by a friend sent to a military labor camp.

Finally freed from her backbreaking toil in the fields, Liu first earned a teaching degree and taught art at the elementary level. She hosted a nationally televised show teaching art to children, gaining fame in her native land. Eventually, Liu enrolled at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where she majored in mural painting—work necessarily inflected with state-sponsored socialist realism. Even as she was compelled to depict Communist propaganda, Liu honed her skills as a painter and mastered the techniques for her large-scale works.

Resident Alien by Hung Liu, 1988 Collection of the San Jose Museum of Art, gift of the Lipman Family Foundation. © Hung Liu

Resident Alien from 1988 offers another self-portrait of sorts, in this case in an American context. Liu reproduced her green card as a 5- by 7.5-foot critique of her immigration experience. The promised land of America dubbed her a “resident alien,” an epithet that screams at the viewer in capital letters across the top of the enlarged card. Liu’s ironic sense of humor emerges here as well; instead of her given name, Liu satirically renamed herself “Fortune Cookie.” Liu viewed the fortune cookie as a hybrid symbol, neither American nor Chinese, and as such denoted her unstable identity and the contradictions of multiculturalism.

Mission Girls 20 by Hung Liu, 2003 Castellano-Wood Family Collection. © Hung Liu

Nonetheless, she transposed her birthdate from 1948 to 1984, the year she immigrated, as a declaration of her freedom and new life; Liu spent an even 36 years living in China and in the United States.

No longer beholden to the strictures of Soviet art, Liu began to explore vibrant colors and dripping pigment woven into the fabric of the painting, which she layered with delicate butterflies, flowers, birds and other decorative motifs derived from ancient Chinese painting. The highly textured, boldly colored 2001 Strange Fruit: Comfort Women is based on a photograph of Korean women forced into sexual servitude by Japanese soldiers during World War II. Liu individualized these mural-sized figures, who are awash in her trademark linseed drips.

“Liu’s signature use of generous amounts of linseed oil to create a veil over her subjects allowed her to activate time, history and memory in her work,” says Moss. “She engages with history through her concept of ‘history as a verb,’ it is ‘always flowing forward.’ Through her linseed drips her paintings perform this idea, bringing her historical subjects into the contemporary moment.”

Nonetheless, she transposed her birthdate from 1948 to 1984, the year she immigrated, as a declaration of her freedom and new life; Liu spent an even 36 years living in China and in the United States.

No longer beholden to the strictures of Soviet art, Liu began to explore vibrant colors and dripping pigment woven into the fabric of the painting, which she layered with delicate butterflies, flowers, birds and other decorative motifs derived from ancient Chinese painting. The highly textured, boldly colored 2001 Strange Fruit: Comfort Women is based on a photograph of Korean women forced into sexual servitude by Japanese soldiers during World War II. Liu individualized these mural-sized figures, who are awash in her trademark linseed drips.

“Liu’s signature use of generous amounts of linseed oil to create a veil over her subjects allowed her to activate time, history and memory in her work,” says Moss. “She engages with history through her concept of ‘history as a verb,’ it is ‘always flowing forward.’ Through her linseed drips her paintings perform this idea, bringing her historical subjects into the contemporary moment.”

When Liu gave talks about her art she was always asked about her drips and her circles, the second hallmark of Liu’s work, says her husband, art critic Jeff Kelley. The thickly rendered 2003 Mission Girls 20—a series that stems from a single 19th-century Chinese photograph of orphan girls that Liu divided into 29 smaller canvases—features powerful gestural circles. Those circles are meant as a form of visual punctuation that brings viewers back to the physicality of the paint.

Migrant Mother: Mealtime by Hung Liu, 2016 Collection of Michael Klein. © Hung Liu

“Usually made with a single stroke, Liu’s circles are like endless lines, or lines closing on themselves (like a snake eating its tail),” Kelley writes. “They enclose everything and nothing, sometimes canceling an image (like a face) or connecting several. Usually riding the surface of the painting, the circles remind us of tattoos or thought bubbles. In Buddhist philosophy, as in a circle, inside and outside are just illusions.”

Her final major series, “After Lange,” was based on Dorothea Lange’s Dust Bowl photographs, including outtakes of the iconic image popularly known as Migrant Mother. Liu finds resonance in her predecessor’s refugee women and their children with her own story of labor and survival—along with Lange’s mastery at capturing the humanity of her subjects. With her brushstrokes, Liu breathes life into images from old black and white photographs that she’s collected. She believed in women as the lifeblood of the family; she honors those female itinerants who provided strength during the grueling move from Oklahoma to California and those in her own family. So too, Liu plays on Mao’s proclamation that women hold up half the sky. A mountain symbolically sits on the back of Liu’s mother in the shaped 1993 portrait Ma.

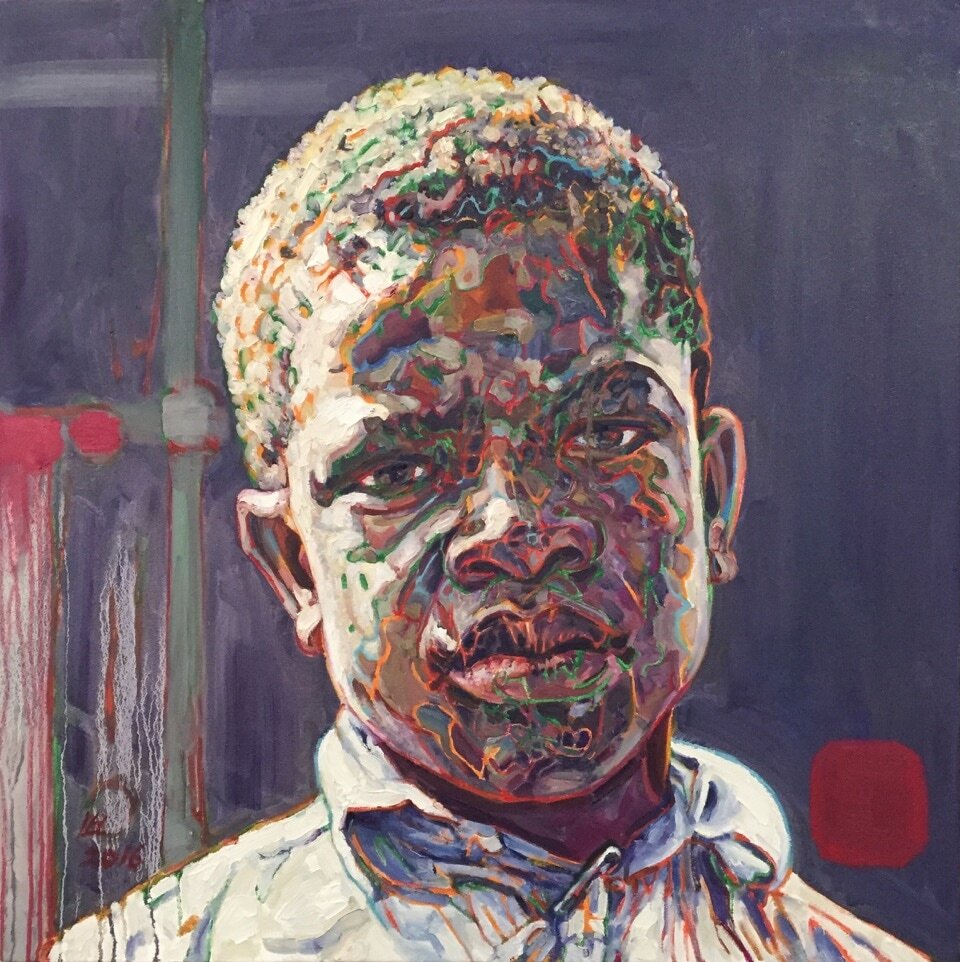

When Liu moved from Chinese subjects to American subjects she developed a new style, but the force of her empathy remained the same. Another painting in the “After Lange” series, Laborer: Farm Hand (Clarence Weems) from 2016, portrays a worn-out African American boy in the deep south. Colorful “topographical mapping” over the face of her subject serves as a visual metaphor: “They are our scars, our nerves, our stories,” she has said.

Clarence Weems’ niece, artist Carrie Mae Weems—Liu’s classmate in San Diego and the first African American artist to have a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum—wrote an appreciation of Liu’s art for the exhibition catalog: “Through sheer grit, muscle, and determination, she deploys the wiles of sublime beauty to captivate, pull us in, and bid us look.... Liu tells a tale rarely heard or seldom seen. Her paintings, breathtaking in their beauty, use unsurpassed skill to reveal the push of a people caught in the turmoil of upheaval, people tapped by oppressive systems meant to control.”

Laborer: Farm Hand (Clarence Weems) by Hung Liu, 2016 Collection of Josef Vascovitz and Lisa Goodman. © Hung Liu

Liu’s counter revolutionary impulse as a young woman in China has extended to a revolutionary posthumous present. The National Portrait Gallery is working now on the accession of Liu’s last two self-portraits.

Mourning the fresh loss of his wife, Kelley wrote of Liu’s final self-portrait The Last Dandelion, for the wall label accompanying its recent installation: “To look at those bright and living eyes, like orbs in a deep endless night, is to remember that Hung Liu lived her dramatic, epical life as a painter, which remains alive, and whose last dandelion will never drift away.”

We can only hope that these crucial additions to the museum’s permanent collection signal an ongoing revolution, one where women artists and minority artists—and the female experience—more frequently find a presence in the storied museum.

"Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands" is on view at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery through May 30, 2022.